At least since Donald Trump's 2016 win, many people have asked themselves a simple question: why do voters – especially those poorer ones – vote for politicians called the populist right?

Basically, we have 2 popular answers. The first says that any voters simply corresponds to that part of the right hand. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

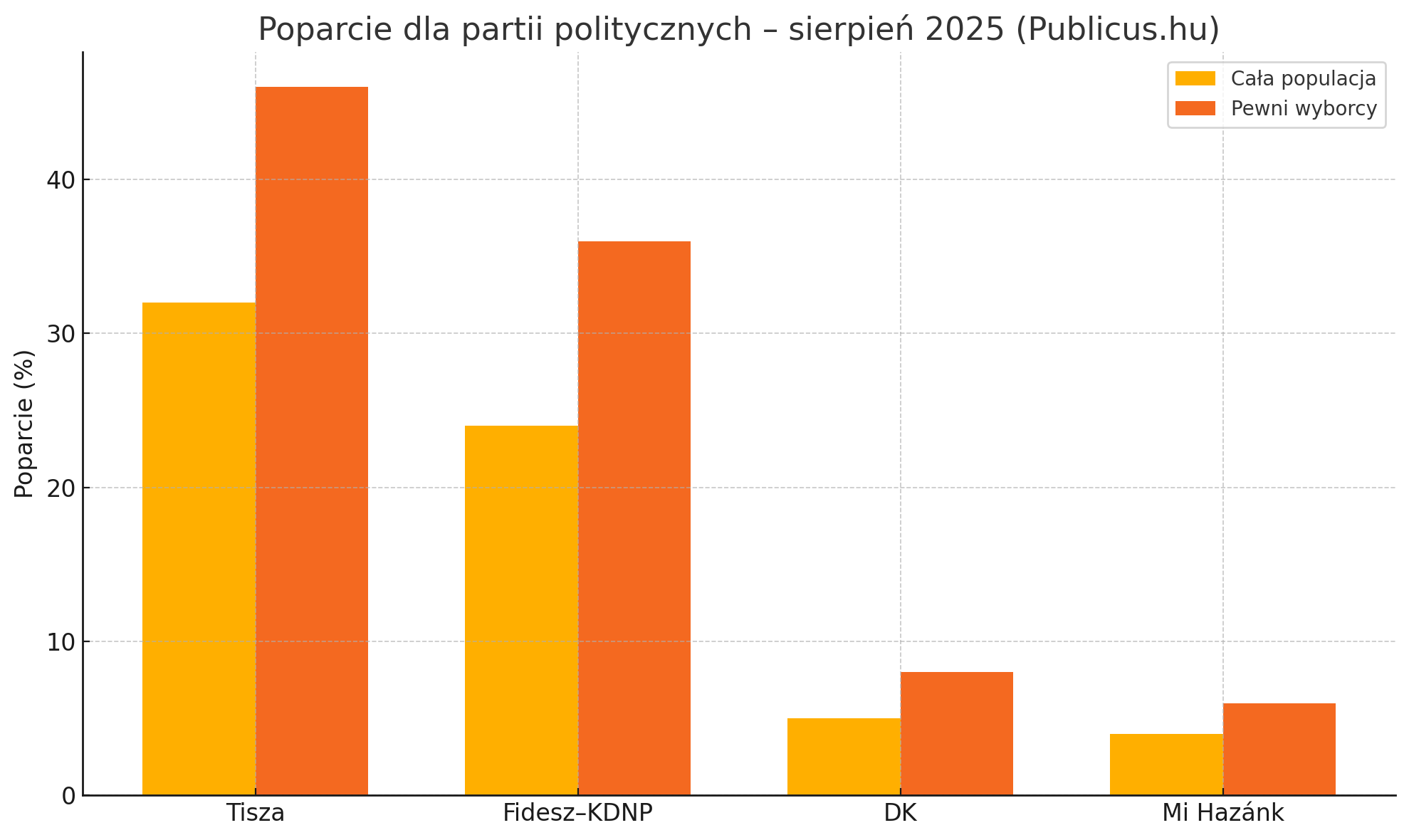

There is most likely a part of it – just look at the polls. In Poland, many inactive do not accept even partnerships for minorities, not to mention increasing dislike of migrants.

The second explanation is that the vote for politicians specified as Trump, Kaczyński, Mentzen or Farage is actually a vote against the elite. Promises Failed politicians, rising social inequalities and collapse of public services caused voters to lose assurance in the state and the current mainstream parties. So they are ready to vote for the "anti-system right" – anti-system right only by name, due to the fact that in fact most of these politicians are an integral part of the system.

This explanation seems even more accurate than the erstwhile one. We've even got a number of tests economists and polytologists indicating that social inequalities Indeed, they drive the popularity of the far right.

However, both of these explanations presume that there is simply a smooth flow of information between what politicians say and do and what voters know about it. That people are more or little aware of who is liable for what – and on this basis they decide whether they support it, or whether they are angry at it.

This assumption, at least in relation to any voters, is questionable.

I don't just mean misinformation, although it is most frequently referred to as a symbol of problems with the information system. Sure, misinformation is simply a serious problem. But it is only part of a wider phenomenon: a general disturbance in the circulation of information in society.

Common sense is in our heads

Take my favourite example: Investigations The Polish economical Institute, which shows that Poles have a light thought of the structure of state spending. They inflate administrative costs 3 times and at the same time underestimate the scale of another expenditure, mainly on pensions and pensions.

This is not due to the fact that individual deliberately misled them in this substance – it is not the effect of any disinformation action from a peculiar organization or organization. The problem is deeper and has 2 levels.

Firstly, there is no affirmative information infrastructure. If anyone wants to check the government's budget structure, then... good luck. There is no simple, friendly way of reaching these data – let alone uncovering them in the form of transparent, graphically attractive compilations. The media besides seldom informs about it, most frequently the subject appears during the pastry research.

Secondly, since there are no reliable sources of information, most people trust on intuitions—so-called Common sense. And this common sense is actually a collection of myths repeated by the full past of the 3rd Republic: that the state is expanded, the officials are lazy, taxes are gnawing at us, and expenditure must be cut. These beliefs were promoted by politicians of different options and by most media. This is what modern economical cognition is based on today. So people presume that the state spends immense amounts of money on administration and that it is there that the top savings can be found.

The specified focus on combating misinformation will not solve specified problems with the flow of information in society.

Politics? I'm not interested.

When we talk about Trump's win, we cannot overlook the fact that he had a immense advantage among voters who do not track political information all day – not in conventional media, not on the Internet. By one of the polls The pre-election group had 53% of support and Biden had only 27%. No another group of voters – people who learned from YouTube, social media, websites, cable television, national tv and newspapers were besides checked – did not support Trump so much.

American publicist Ezra Klein likes to repeat that the main dividing line in American politics does not run between democrats and Republicans, but between those who are curious in politics and those who are not curious in politics at all. The erstwhile underestimate how many of the second are—and how small they know about matters which for those active politically seem obvious.

Indeed, American politics are a good example. More opinions are being conducted in the US than in Poland, so it is easier to show the scale of the problem with the circulation of information. Pew investigation Center poll of 2023 showed that as many as 37 percent of Americans could not correctly pinpoint which organization had the majority in the Senate. More people didn't know who was controlling the home of Representatives.

Or take “Inflation simplification Act” — America’s largest climate investment package, adopted as president Joe Biden. Shortly after his adoption, the CBS station commissioned pollWho checked how many Americans have heard of the President's climate action. It turned out that even among those voters for whom the issue of climate was a priority, until half had no greater thought of what the president had done (or did not do) in this matter.

Of course, the name of the law on inflation simplification did not help. Democrats needed the voice of Conservative Senator Joe Manchin, who was not peculiarly curious in saving the climate – but he was very curious in inflation. respective anti-inflation solutions were introduced into the bill and its name was changed to make the senator happy.

This is another problem with the flow of information – besides present in Poland. The deficiency of transparency of the legislative process means that most citizens do not realize who makes the decisions and what the consequences will be.

The Americans are the actual masters of complicating politics, that's true. For example, they have introduced so many restrictions on the President's power – contrary to the stereotype that he is "the most powerful man in the world" – that 1 of the fewer ways to implement a major improvement is to adopt a budget bill erstwhile all 2 years. A simple majority is adequate to carry it out, so all presidents enter the key points of their agenda into it.

The consequence is confusion with voters who do not realize why there are records of climate, inflation and yet artificial intelligence in 1 bill (this year the Republicans want to reduce taxes in the budget bill, cut wellness expenses and... ban individual states of regulation of the artificial intelligence sector for 10 years).

In this respect Poland has a more sensible model: usually a simple majority in the Sejm is enough, and even if the president vetoes the bill, the procedure for rejecting veto is besides transparent.

However, we should learn 1 crucial lesson from American experience: people do not follow political information on a regular basis. They are not aware of the complexity of negotiations or decision-making procedures. individual who is curious in these matters on a regular basis should not presume that the remainder of society has akin cognition of what politicians or parties do good or bad.

Education? Don't make me laugh.

It is only erstwhile we realize how deep the problems of deficiency of reliable information in society are that we can seriously start doing something about it.

For example, we will rapidly realise that the most frequently proposed solution – "we request more education" – has limited effectiveness in this case. due to the fact that what would that education be about the structure of budget spending? The state budget is changing. What we learned 15 years ago at school may be completely out of date today.

So it's not about education, it's about creation of a reliable and accessible information infrastructure. The natural candidate for specified a function would be public media — but we all know what their condition is. During the regulation of the Law and Justice were terrible, present they are simply weak.

This was shown perfectly by the last election campaign. The Civic Coalition could not defy the temptation to usage public media to – let us call it plain – propaganda for its candidate. This empty space has entered Channel Zero. Krzysztof Stanowski. Of course, this channel is not an example of honesty or impartiality either. To any extent, however, its popularity is due to the weakness of public media.

Because any of the things that the channel does – like a fewer hours of conversations with all candidates – should do public media. Only professionally: well prepared interviews conducted by competent journalists, made available online.

This is just a tiny example, but it shows how easy we miss opportunities to improve our information infrastructure.

The exact same charge can be raised against government websites. Nothing serious is being done so that citizens can easy and rapidly find the basic information, even if it is about precisely what the taxation money is going for, or how much of our contributions are truly ‘overeating’ ZUS.

Much to improve

This must be made clear: after the full digital revolution – the Internet, smartphones, social platforms – we are inactive very, very far from the enlightened utopia, in which well-informed citizens actively participate in the political decision-making process.

Of course, it can be blamed on people – that they are passive, that they are not curious in politics, that they easy give in to misinformation, and this utopia can never be full realised. But you can besides ask yourself, what have we as a society done wrong?

Childic admiration for corporate social media. A non-reflective repetition of phrases specified as "must be educated". Accepting that public media is simply a organization spoil. No emphasis on transparency of political procedures. Media repeating silly phrases about “a blown-up country”.

These are just a fewer examples of things that do not arise from any historical necessity, but are a consequence of concrete decisions – especially the decisions of those who had the most to say about it: politicians, the heads of the top media and their sponsors.

![A gdyby śmierci nie było? [o „Trzecim królestwie” Knausgårda]](https://krytykapolityczna.pl/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Szablon-rozmiaru-obrazkow-na-strone-2.png)