"We rise the sail of the rebellion of the creative spirit, which was to be condemned to death by pushing into the abyss of nothingness. We are going against this nothingness, against the wasteland in which the Polish people were pushed.” [1].

Jan Stachniuk

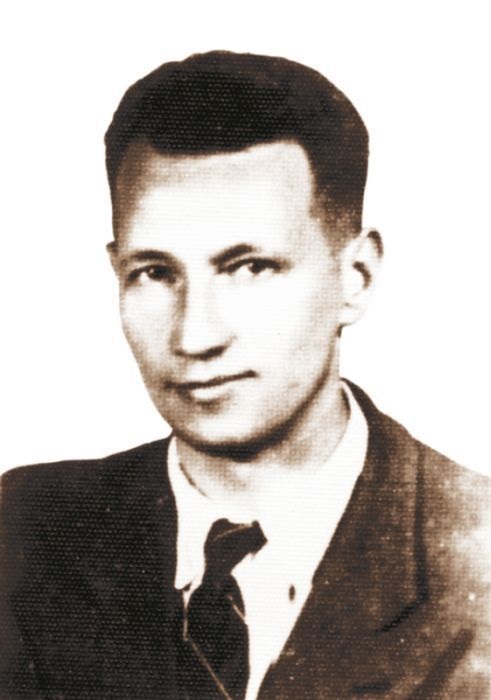

Analyzing the past of Polish political thought, 1 cannot ignore the figure of Jan Stachniuk (pictured), being 1 of the most interesting and first political thinkers, historians and cultural theorists.

The fact that Stachniuk's character is now mostly forgotten may be due to the fact that ideas he preached were uncomfortable for both left-liberal and conservative-Catholic environments. It should be stressed that both Stachniuk and his co-workers focused around the magazine “Zatruga” went beyond conventional political and ideological divisions, eluding established patterns and stereotypes. Given the tiny numbers, the "Second" environment was highly active and intellectually fruitful – its achievements were not only made up of works Jan Stachniukbut besides journalist Antoni Wacyk, Janina Kłopocka, Tadeusz Thenor brothers. Józef and Stanisław Grzanków in the diary “Zapruga” published between 1937 and 1939. The analysis of Stachniuk's legacy was carried out by recognised researchers specified as: Prof. Bogumił Grott, Prof. Jacek Majchrowski, Prof. Jan Skokyńskior Dr. Jarosław Tomasiewicz. At the same time, Stachniuk's character is inactive an inspiration for many nationalists who, for various reasons, stay skeptical or critical of the function of the Catholic Church in Polish history, or the influence of Christianity on Polish national tradition and culture.

Jan Stachniuk was born on 13 January 1905 in Kowl in a railway family. After graduating in 1927, he moved to Poznań, where he began his studies at the School of Commerce. Here he besides became active in political activities in the Polish Democratic Youth Union – an organization connected with the sanctioning in which strong leftist and syndicalist influences were present. Despite this, in later times both Stachniuk and the environment in which it rotated – it referred more broadly to the tradition of early endection, including, above all, the legacy of its classics Roman Dmowski and Zygmunt Balicki. As Prof. Bogumił Grott wrote in his work “Dylematy of Polish Nationalism. Returning to tradition or rebuilding the national spirit": "It can be assumed that the second-captured plots and values appropriate to the "old" endeci from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries were sincere and authentic. It was about the realm of values. In the passages of people's reasoning formed in the second half of the 19th century, in a time of Scientism and expanding belief in man's capabilities, and his teaching, Zatruga saw a building block for her own ideas that could be used" [2].

In 1933, Stachniuk published his first book “Collectiveism and Nation“ in which he advocated, among another things, the introduction of a strategy of planned economy, in order to extract Poland from stagnation and economical backwardness. Stachniuk already noted that the essential condition for modernization and improvement of Poland is to change the mentality and transformation of the national character of Poles, which referred to to any degree besides included in "Thoughts of a Modern Pole” Roman Dmowski. In a time of large economical crisis, the conviction of the imminent collapse of capitalism was rather common. However, Jan Stachniuk did not request a return to pre-capitalist forms of production and the spread of ownership, as for example Adam Doboszynski and many another National organization activists (especially ‘young’ factions) and secessionist groups. Stachniuk advocated fast industrialization of Poland and collective production methods. In 1935, Stachniuk's second work was published – "Heroic community of the people’, in which he developed his economical and social demands.

In November 1937, the first issue of the monthly issue “Zapruga” was published, whose subtitle was “the writing of Polish nationalists”. Apart from Stachniuk, the editorial board besides included: Stanisław Grzanka, Józef Grzanka, Ludwik regulation and Tadeusz Then. The character and ideological profile of the writing is much mentioned in his first issue: “We are Polish nationalists who, in the current reality, are Polish-named suffocators. We choke in the fumes of mediocrity and smallness, in the fumes of spiritual poorness and material poverty. Seeing what surrounds us is humiliating. For our unfulfilled hunger, for smallness, for misery, for humiliation, we accuse Polish historical past, we rebel against it" [3]. The publications published in "The Second" were criticised by both the left and the right. While the leftist communities saw the writings of fascist influences in the publications, the national-Catholic and conservative circles accused Stachniuk of anti-Catholicism and the postulate of economical solutions adopted in the USSR.

In August 1939, Jan Stachniuk published a paper “History of past – explanation of interior improvement of Poland”, in which he attempted to show the harmful effect of Catholicism on the Polish national character, by promoting inactivity, Aprilism and anti-Community attitudes. According to Stachniuk, they were not biological, but cultural and spiritual factors that determined the pace of civilizational improvement of individual countries over the period of history, and the stagnation and regression of Catholic countries in Europe opposed the dynamic improvement of Protestant states, indicating clear inspiration by thought Max Weber.

During the war, Jan Stachniuk stayed in Warsaw, where he became active in the creation of the National Zriw organization and its military formation under the name of the Independent Poland Personnel, subordinate to the National Army in 1943. Stachniuk's closest collaborators were erstwhile activists of the National Workers' organization at the time – Zygmunt Felczak and Felix Widy-Wirski. In 1944, Stachniuk fought in the Warsaw Uprising, during which he was wounded 3 times. The war experiences resulted in a publication entitled "The Issue of totalizm", in which he referred to the assessment of movements and ideologies of a totalitarian character (now referred to as totalitarian).

Against the claims of Catholic adversaries centered around Sophia Kossak-Szczucka – Stachniuk explicitly condemned Hitlerism and its related ideologies. This is evidenced by the passage of the abovementioned publication: “If the civilized humanity knew what fascism and totalizm were to be 10 years ago and what it would lead to, it would undoubtedly be able to master the coming flood, laying impenetrable dams in its path. Unfortunately, what was then to be done with a tiny amount of power, present must be paid with immeasurable blood sacrifices and feeding the moth of war, devouring the fruits of the efforts of full generations"[4].

According to Stachniuk, totalitarian movements utilized the energy and vital forces of societies to act destructively, alternatively of utilizing them to intensify modernization and cultural processes. "The primitive drive for power and the drunkenness of power is irresistibly magic to the minds of millions. We have here described the current drama of humanity: the growth of causative power in the temptation of bare force and power. Its classical incarnation is modern Nazi”[5].

After the war ended, Jan Stachniuk tried to find himself in a fresh reality, and the beginnings of these efforts were promising. It was the most intense and creative period of his activity. It was then that he published his most outstanding works: “Humanity and Culture" and “Christianity and humanity”, in which he systematic his philosophical concepts. According to the doctrine of Jan Stachniuk, referred to as "culturalism" the axis of human history, was the eternal conflict of culture against its opposing processes, referred to as "the best culture". According to Stachniuk, human life only makes sense erstwhile it is creative and full integrated into cultural processes – otherwise it only means bioving, that is, sterile and non-reflective life for the duration itself. The unit torn from the process of creating culture is oriented solely on the thoughtless and parasitic consumption of the cultural heritage of generations. Biogetation means limiting the existence of an individual to repetitive biological life processes.

Stachniuk's attitude to Christianity (and in peculiar to Catholicism) was unequivocally negative – in Catholic religion he distinguished six elements which he considered to be "wspukultural": personalism (the will of pure physiological individual – life for the life itself), moralism (the final improvement of interior same without being translated into the environment), omnivorousness (the negation of fighting in the name of love for all, including enemies), spiritualism (the breaking distant from the temporal affairs and placing the purposes of the individual in the afterlife), nihilism (the negation of the planet of culture and cultural processes), hedonism (the drawing happiness from pure vegetation).

Interestingly, Stachniuk besides coined the concept of “Laician culture”, to illustrate attitudes and behaviours aimed solely at satisfying material needs and achieving physiological happiness. According to Stachniuk: “Laick culture will play an increasingly crucial function in the future. The main reason for this is its dynamics, resulting from the tasks it undertakes. The full span of the cross should be limited only to protests and warnings that fewer perceive to. Laick's culture, on the another hand, has open ways to realize its perfect – happiness in this world. It is open to the possible of an earthly paradise, a naive belief that it can be realized.”[6] John Stachniuk's quoted words proved prophetic if we look at modern Western civilization, based on materialism, consumerism, and hedonism.

In the political aspect, the postwar situation of Jan Stachniuk and his associates initially led to average optimism. In 1945, the National Zriw organization submitted to the National Council. Stachniuk besides shared the socio-economic demands of post-war Polish authorities and accepted the country's overall imagination of development. He only warned that economical changes must be reflected in the intellectual changes of Poles, pointing out that the construction of a fresh order can only win if "collective enthusiasm" is implanted in society. In support of the post-war order of Stachniuk, he besides hoped that in a socialist state the alleged "traditional sector" would be removed from the influence, including Catholic-conservative environments. At the same time, he attempted to bring about any form of legalization of the erstwhile squad environment (e.g. he tried to postulate the creation of the Institute of National Culture Reconstruction), which did not bring the expected result.

Although Zygmunt Felczak was a associate of the National Council and Vice-Vice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voice-Voity, and then Under-Secreate in the Ministry of Information and Propaganda, their influence was limited. Felczak's death and Widy-Wirski's political fall (due to the run against right-nationalist deviation in the party) yet buried Stachniuk's political chances. He was arrested in 1949 and sentenced to 15 years imprisonment for alleged "participation in the fascism of the country" (Beniamin Wejsblech prosecutor demanded death penalty). After his release from prison in 1956, Jan Stachniuk was a sick and incapable to live on his own – he died in a healing facility in Joy on August 14, 1963.

Michał Radzikowski

[1] Jan Stachniuk, “Humanity and Culture”, Wyd. “Toporał”, Wrocław 1996.

[2] Bogumił Grott, “Dylematy of Polish Nationalism. Return to the tradition or reconstruction of the national spirit", Wyd. “von borowiecky”, Radzymin 2013.

[3] Stanislaw Grzanka, “Who are we?”, No. 1 of the letter “Zapuga” XI 1937.

[4] Jan Stachniuk, “The Question of totalizm”, Wyd. “Toporał”, Wrocław 1990.

[5] Jan Stachniuk, “The Question of totalizm”, Wyd. “Toporał,” Wrocław 1990.

[6] Jan Stachniuk: “Christianity and humanity”, Wyd. “Toporał”, Wrocław 1997.

Think Poland, No. 5-6 (29.01.-5.02.2023)